80-629-17A - Machine Learning for Large-Scale Data Analysis and Decision Making (Graduate course) - HEC Montreal – Homework (2018/10/12). Option Model – The EM algorithm

The Expectation Maximization (EM) is a general-purpose iterative algorithm used in the calculation of maximum likelihood estimates in cases of incomplete data. The basic intuition for the application of EM is when the likelihood maximization of the observed data is difficult to compute but the enlarge or complete case, which includes the unobserved data, makes this calculation easier. The iterative stages are usually called the E-step and M-step. This is a very popular algorithm used in the parameter estimation in models involving missing values or latent variables.

Preliminary considerations:

Having the training set { } of observed independent examples and denoting { } the set of all latent variables and the set of all model parameters, we need to fit the parameters of model to the data. The corresponding log likelihood is given by:

We can observe that the summation over the latent variable appears inside the logarithm and this sum prevents the logarithm from acting directly on the joint distribution. Also, the marginal distribution does not commonly result in exponential distribution even if the joint distribution belongs to the exponential family (Bishop, 2006). In this regard, the maximum likelihood solution becomes a complicated expression often difficult to calculate. However, if the latent variable were observed, the complete case would be { } and the respective log likelihood would take the form of . The maximization of this complete-data log is assumed to be easier to calculate. In practice, we only have the incomplete data set and what we know about would be related to its posterior distribution .

Notes: the current discussion is centered around the summation over . In case is a continuous latent variable, the summation is replaced with an integral over . The semicolon in the join probability denotes a conditional on a given realization of the parameter.

Description:

We have introduced the likelihood (Ng, 2017):

For each , we denote as some probability distribution over the ’s ( ). Then we have that:

In step 2, we simply add to the numerator and denominator. In step 3, Jensen’s inequality is used with the following considerations:

- as the log function is concave (if then ), then ; and

- the summation term in step 2 can be considered as the expectation of quantity with respect to drawn according to the distribution given by .

This can be also represented as where the subscript indicates that the expectation is with respect to over . Finally, the Jensen’s inequality gives us

and we use this to go from step 2 to step 3. Critically, the result in step 3 gives us a lower bound for for any set of distributions .

We hold parameters at any given value (or current guess) and analyze the best choice of . Intuitively, the best choice is the one that makes the gap between the lower bound of and the tightest. The Jensen’s inequality becomes the equality when is linear or is constant. Therefore, for a particular , the derivation in step 3 becomes an equality (the gap becomes zero) when the expectation is taken over a constant (log function is not linear). In other words, we need that

for a constant that does not depend on . We can assure this by choosing

Because is a probability distribution we must enforce that . Then we obtain the following derivations:

This result implies that, when setting the ’s as the posterior distribution of conditional on and a general parameter value , the log likelihood is equal to the lower bound (the tightest bound possible), making a tangential contact at the given . This is called the E-step. For the next stage, the M-step, we try to maximize (“push-up”) the lower bound of log likelihood as stated in step 3 with respect to parameters in while keeping from the E-step. The E-step and M-step are repeated until a measure of convergence in the computation of lower bound or parameters is achieved.

In summary, EM algorithm would be implemented as:

- For a joint distribution governed by parameters , we try to maximize with respect to .

1- Choose initial values for .

- Repeat 2 and 3 until convergence:

2- E-step: for each 𝑖

3- M-step: Set

In the E-step we use the current value or guess to find the posterior distribution of the unobserved/latent data . Our knowledge of is given only by this posterior distribution. In general, we cannot use the complete-data log likelihood, but we can use instead its expected value under the posterior distribution of the latent variable. In the M-step we maximize this expectation with respect to – as found in the complete-data - but using the expectation given by posterior found in the E-step. We can also show that, in the M-step, the maximization target function can be stated as: . It is because the denominator in the log term of M-step’s target function does not depend on the that we try to maximize and can be considered as constant during the optimization process.

The lower bound of can be also expressed as (Murphy, 2012), where:

This is just a direct consequence of the properties of expectations and the log function (log a/b = log a – log b) as well as the Shannon’s entropy definition ( ). As stated before, does not depend on . Furthermore, through the steps in Annex A, Murphy (2012) decomposes the lower bound (inferred in (3)) as the sum over of the terms and obtains:

We observe that log does not depend on and the lower bound is maximized when the Kullback–Leibler divergence () term is zero. This implies that:

- the best choice for is to be set equal to as the KL divergence (relative entropy; the measure of divergence between two distributions) is zero only when the both probabilities are the same (KL is positive when the probabilities are different). This is equivalent to the “ best choice of ” step described before.

- when the term is zero, lower bound is maximized and it is equal to log for a given choice of .

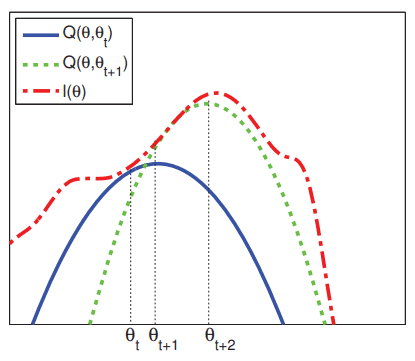

For the E-step: because is not known, we chose an estimated and set . By making the divergence zero, now the lower bound equals the function at . When considering the sum over we get that the lower bound of denoted as equals . Once the gap is zero, the next step is to “push-up” the lower bound. For the M-step: to “push-up” the lower bound, we maximize (we can drop ) with respect to while keeping . We get a new estimate of the parameters to be used in the next E-step:

The results are equivalent to those presented before; however, this representation helps understand the iterative process in terms of the KL divergence:

when we maximize the lower bound in the M-step, the lower bound increases but the will increase more due to the KL divergence.

The reason for this is that the maximization of the lower bound uses the distribution based on to find the new .

This will increase the KL divergence as the new posterior distribution will be different than that of .

In this regard, unless is at maximum already, the increase in is at least as high as the increase of the lower bound in the M-step. The iterations are needed to until convergence.

Note: Murphy (2012) starts defining to later introduce . This is just to highlight that depends on the current values of .

Source: Murphy (p.365, 2012). The dashed red curve represents the observed-data log likelihood while the blue and green lines represent, respectively, the lower bounds and tangential to at and . The E-step makes to touch at by assigning . In the M-step we find by maximizing . The difference between and correspond to the divergence. In the next E-step we produce a new lower bound by setting . E-step and M-step are repeated until convergence.

Proof of convergence:

We would need to show that the EM iterations monotonically increases the observed data log likelihood until it finds a local optimum. First, we have that, for a general , (the lower bound is less or equal to , particularly for ). Then, we have that, after the lower bound is maximized in the M-step, . Finally, as in E-step, . Therefore, we have:

Remark on coordinate ascent (Hastie et al., 2009): By defining

we can observe that , as presented in (3). Then the EM algorithm can be understood as a coordinate ascent on J: The E-step maximizes with respect to and the M-Step maximized with respect to .

Properties:

Some interesting properties of EM are:

- Easy implementation both analytically and computationally as well as numerical stability. Easy to program and requires small storage space.

The monotone increase of likelihood can be use for debugging. The cost by iteration is relatively low compared to other algorithms. Among it uses, it can provide estimates of missing data (missing at random) as well as to incorporating latent variable modelling (McLachlan et al., 2004).

- In addition, the EM algorithm can compute also Maximum a Posterior (MAP) estimation by incorporating prior knowledge of the estimate .

For this, the only modification needed is in the M-step, where we would seek to maximize (Bishop, 2006).

- Regarding the optimization, it is possible to the log likelihood has multiple local maximums.

A good practice is to run the EM algorithm many times with different initial parameters for . The ML estimate for is that corresponding to the best local maximum found. Some drawbacks are (McLachlan et al., 2004):

- Slow rate of convergence.

- The E- or M-steps may not be analytically tractable.

- The EM algorithm does not automatically provide an estimation of the parameter’s covariance matrix. Additional methodologies are needed.

Competing methods (Springer and Urban, 2014):

Newton methods for optimization can be also considered for maximum likelihood estimations. Newton methods work on any twice-differentiable function and seemingly converge faster than EM implementations. Nevertheless, Newton methods are costlier as it involves the calculation of second derivates-Hessian matrix.

Example - Mixture of Gaussians

The motivation for Gaussian mixture models (GMM) is to achieve a richer class of densities by linear superposition of Gaussian components of unknown parameters. This model can be expressed as with denoting the mixing coefficients related to K components ( and ). The mixing component corresponds to a type of subpopulation assignment of the data. As this assignment must be learnt by the model, GMM is a form of unsupervised learning.

Nevertheless, the log likelihood of this original model is difficult to maximize. If we use a latent variable [a 1-of-K binary representation: is 1 if the element belongs to the k distribution and is 0 while satisfying {0,1} and ], we get with marginal distribution over (or equivalently ) and Gaussian conditional distribution of over a particular value of . We can see that for every observed data point there is a latent variable and as equally important, now we can work with the joint distribution in the EM algorithm. The most important realization of the latent variable version of the GMM is that the expected value of under the posterior distribution is equivalent to and can be written as:

For the EM algorithm, we start with some guess values of : and iterate until convergence: E-step: calculate . M-step: maximize with respect :

When replacing the marginal and conditional described above, we get:

One consideration is to avoid solutions that collapse in singularity (infinite likelihood when and equals one data point). MAP estimation with priors on can help with this potential problem (Bishop, 2006).

References:

- Ng, Andrew. CS229 Lecture notes 8 - The EM Algorithm. 2017. http://cs229.stanford.edu/notes/cs229-notes8.pdf

- Ng, Andrew. CS229 Lecture notes 7b - Mixture of Gaussians and the EM algorithm. 2017. http://cs229.stanford.edu/notes/cs229-notes7b.pdf

- Murphy, Kevin P. Chapter 11 Mixture Models and the EM algorithm. Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective, The MIT Press. 2012.r

- Bishop, Christopher M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (Information Science and Statistics). Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg. 2006.

- McLachlan, Geoffrey J.; Krishnan, Thriyambakam; Ng, See Ket. The EM Algorithm, Papers. Humboldt-Universität Berlin, Center for Applied Statistics and Economics (CASE), No. 24. 2004.

- Hastie, Trevor; Robert Tibshirani; J H. Friedman. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction. 2009.

- Springer, T., Urban, K. Numer Algor. Comparison of the EM algorithm and alternatives. Vol. 67, Issue 2, pp335. 2014.